|

| |

| 12. Mai 2011 |

Immer mehr Plastikmüll bedroht Meeressäugetiere

und Seevögel entlang der Küste von British Columbia |

| |

| Wissenschaftler der University of British Columbia, der University of St Andrews, der Raincoast Conservation Foundation, von Oceans Initiative und Environment Canada arbeiteten zusammen, um die Häufigkeit des Vorkommens von Plastikmüll im Meeresgebiet vor BC zu erfassen und die hierdurch ausgehenden Gefahren für Meeressäugetiere zu untersuchen (Williams, R. W.; Ashe, E.; O’Hara, P. D. [2011]; Marine Mammals and Debris in Coastal Waters of British Columbia, Canada; Marine Pollution Bulletin; In press). Immer mehr Styroporabfälle, Plastikflaschen, Plastiktüten und anderer Plastikmüll treiben auf dem Meer vor der Küste und bedrohen die Meerestiere. Gerade der Nordostpazifik ist voller Plastikmüll und mancherorts befinden sich riesige Müllansammlungen auf dem Meer und werden von den Meeresströmungen zu flächendeckenden Müllteppichen zusammengeschoben. Manche Meeresforscher wie z. B. C. J. Moore sprechen bereits vom „Great Pacific Garbage Patch“. |

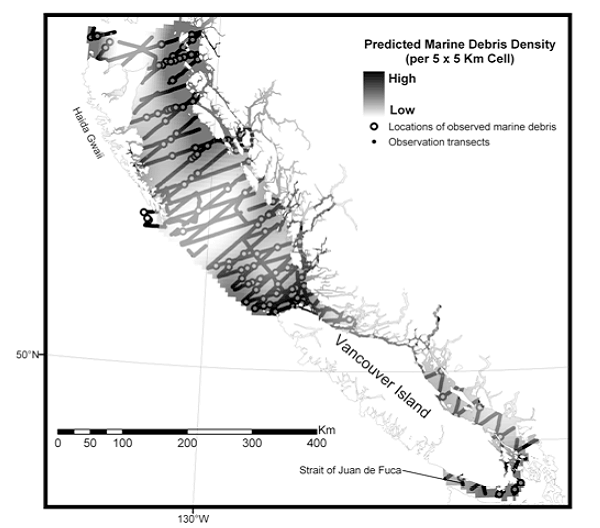

| „The study, part of a larger effort to survey marine mammals, estimated that the inshore waters of coastal British Columbia are filled with approximately 36,000 pieces of garbage with the most common form being Styrofoam, followed by plastic bottles and plastic bags. Marine debris can pose a threat to birds and mammals that accidentally consume garbage, thinking that it is food or become entangled in lines or mesh. A third, but little studied area of concern, is the sublethal effect from plastic’s toxic properties“, heißt es in einer Pressemitteilung der Raincoast Conservation Foundation zu dieser Studie (Study assesses scope of plastic pollution in waters of British Columbia, Canada). „While there is evidence to suggest that the problem of marine pollution is pervasive, most animals that die from consumption or entanglement do so at sea, and their carcasses are rarely found or analyzed“, erklärte Dr. Rob Williams. „There have been few attempts to quantify the scale of the marine garbage problem.“ Ziel der Studie war die Erfassung, wo sich wie viel Plastikmüll im Meer angesammelt hat (vgl. Abb. 1), die Erfassung der Gebiete, in denen sich das hauptsächliche Vorkommen von Meeressäugetieren mit den hohen Ansammlungen von Plastikmüll überschneiden und die Identifizierung von sogenannten Hochrisikogebieten für Meeressäugetiere. |

| |

| Abb. 1 |

|

| Density of marine garbage in the waters of coastal BC. Darker areas contain higher density of debris. Waters off Prince Rupert, Langara Island, Cape Scott and Victoria show highest garbage concentrations. Zigzag lines are ship transects, and dots are sightings. |

| |

| „Surprisingly, marine plastic density was greatest in remote coastal waters such as those off Prince Rupert, Langara Island and Cape Scott rather than urban areas such as Vancouver,” sagte Erin Ashe. “These areas are habitat for Pacific white-sided dolphins, humpback whales and elephant seals, among others. One of the highest risk areas for BC’s endangered fin whales was off Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve.“ |

| Die Studie macht auch Vorschläge für eine bessere Evaluierung des Risikos, welches von diesem Plastikmüll für die Meeressäugetiere ausgeht. „BC elephant seals have been recovered with Styrofoam in their stomachs and a grey whale recently recovered in Washington State had gallons of marine debris in its stomach“, sagte Misty MacDuffee von der Raincoast Conservation Foundation. „Are animals in BC dying from ingestion or entanglement, and if so, on what scale? We need a better handle on the threat that marine debris is posing to our marine wildlife.“ |

| „Estimates from California suggest that 60 – 80 % of marine debris has its origin on land. So it is far easier and cheaper to reduce input of garbage than to do clean-up after the plastic has reached the ocean. Allocating funds for volunteer groups to strategically target beach cleanups in these remote, higher-risk areas is one way to reduce the scale of the problem“, teilte die Raincoast Conservation Foundation in ihrer Presseerklärung mit. |

| Nachfolgend finden Sie eine kurze englische Zusammenfassung des Artikels von Williams, Ashe und O’Hara: |

| „Entanglement in and ingestion of synthetic marine debris is increasingly recognized worldwide as an important stressor for marine wildlife, including marine mammals. Studying its impact on wildlife populations is complicated by the inherently cryptic nature of the problem. The coastal waters of British Columbia (BC), Canada provide important habitat for marine mammal species, many of which have unfavorable conservation status in the US and Canada. As a priority-setting exercise, we used data from systematic line-transect surveys and spatial modeling methods to map at-sea distribution of debris and 11 marine mammal species in BC waters, and to identify areas of overlap. We estimated abundance of 36,000 (CIs: 23,000 – 56,600) pieces of marine debris in the region. Areas of overlap were often far removed from urban centers, suggesting that the extent of marine mammal-debris interactions would be underestimated from opportunistic sightings and stranding records, and that high-overlap areas should be prioritized by stranding response networks.“ |

| |

zurück zurück |

|

|