|

| |

| 18. Januar 2014 |

Bärbeobachtungstouren im Great Bear Rainforest bringen BC elf Mal mehr

Einnahmen als die Trophäenjagd – neue Studie des Center for Responsible Travel |

| |

| Das Center for Responsible Travel CREST (Washington, DC und Stanford University) veröffentlichte am 7. Januar eine Studie mit dem Titel „Economic Impact of Bear Viewing and Bear Hunting in the Great Bear Rainforest of British Columbia“. Umweltschutzgruppen in BC hatten schon längst darauf hingewiesen, dass der ökonomische Nutzen von Bärbeobachtungstouren für die Provinz BC wesentlich höher ist als die Einkünfte aus der Trophäenjagd auf Bären. Die Provinzregierung von BC ignoriert diese Zahlen seit Jahren und betreibt eine (mit Steuergeldern mitfinanzierte) Unterstützung der Trophäenjagd. Sie leistet eine aggressive Lobbyarbeit für die Trophäenjagdveranstalter und gerade das für die Jagd zuständige Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations unter Minister Steve Thomson gilt als einseitige Interessenvertretung der Guide Outfitters Association of BC und der BC Wildlife Federation, der beiden großen Organisationen der Jägerschaft. Seit Jahren behauptet das Ministerium von Steve Thomson, die Trophäenjagd sei aus ökonomischen Gründen unverzichtbar. Die Provinz könne nicht auf diese Steuereinnahmen verzichten. Bewusst in Kauf genommen wird, dass dadurch Bemühungen der First Nations, Bärbeobachtungstouren in ihren Territorien anzubieten, geradezu sabotiert werden. Die jetzige unabhängige Studie des CREST räumt mit den immer wieder verbreiteten falschen Behauptungen der Provinzregierung endgültig auf. „Given the sensitivity of the debate and the range of statistics being cited for the value of hunting and viewing, CREST decided to undertake an impartial, academically rigorous analysis to try to nail down the numbers“, sagte Co-Direktorin Dr. Martha Honey von CREST. „Our findings clearly show that bear viewing is today of far greater economic value than bear hunting in the Great Bear Rainforest and that bear viewing is growing, while bear hunting is declining.“ |

| |

|

| Grizzlybär beim Fressen von Seggen in einem Flusstal im Great Bear Rainforest |

© Klaus Pommerenke |

|

| |

| Im Folgenden werden die Hauptergebnisse der CREST-Studie wiedergegeben: |

| „1. The overwhelming conclusion is that bear viewing in the GBF [Great Bear Rainforest] generates far more value to the economy, both in terms of total visitor expenditures and GDP [Gross Domestic Product] and provides greater employment opportunities and returns to government than does bear hunting. In 2012, bear-viewing companies in the GBF generated more than 12 times more in visitor spending than bear hunting: viewing expenditures were $15.1 million while guided non-resident and resident hunters combined generated $1.2 million. The study also finds that organized bear-viewing activities are generating over 11 times more in direct revenue for the BC government than bear hunting carried out by guide outfitters: GDP is $7.3 million for bear viewing and $660,500 for non-resident and resident hunting combined. Further, bear-viewing companies are estimated to employ directly 510 persons (or 133 FTE jobs [Full Time Equivalent for Employment]) per year while guide outfitters generate only 11 jobs (or 4.8 FTE) per year in the GBF. In addition, bear viewing is attracting many more visitors to the GBF than is bear hunting. |

| 2. Bear viewing, a newer activity than bear hunting, is growing rapidly in the Great Bear Rainforest. The study identified 53 bear-viewing companies currently operating in the GBF study area and of these, the great majority reported that their business has grown over the last five years (only one business reported a decline). None said they anticipate business will decline over the next 10 years. In addition, a number of sport fishing and other nature-based tourism companies indicated that they are expanding into bear viewing, and at least one guide outfitter has shifted to bear viewing. From interviews and the site visit it is clear that unguided and unorganized bear viewing, often with drive-in tourists who camp mainly in parks, is also growing rapidly, but this study was not able to assess the size or economic impact of this sector. |

| 3. While it is not possible to determine the total number of tourists who come to the GBF for bear viewing, 25 companies that completed the visitor portions of the CREST survey reported handling a total of 11,369 visitors in 2012. In contrast, in 2012, 186 persons (74 non-residents and 112 residents), hunted grizzly and black bears in the GBF study area. This means that over 60 times more people engaged in bear viewing rather than bear hunting in the GBF. And this number only captures a fraction of the bear viewing sector. This study identified 53 businesses involved in bear-viewing tourism within the study area, plus an undetermined number – in the thousands – of independent tourists who engage in unguided and unorganized bear viewing in the GBF. |

| 4. Bear viewing is a key factor bringing international visitors to the Great Bear Rainforest. CREST surveyed guests who had visited the GBF in 2012 through these 25 companies. Of the 71 visitors who completed the survey, 79 % said that bear viewing was the main reason they visited the GBF. These visitors spent on average 3.8 days in the GBF. Overall, those surveyed spent about one-quarter (26 %) of their total vacation time in BC and 89 % of their time in GBF in bear viewing. |

| 5. In contrast, bear hunting in BC (including the GBF) has been declining since 1980, with less resident and non-resident hunters and fewer days spent hunting. Resident hunting in BC has declined more steeply than non-resident hunting: from 7.5 % of the population in 1980 to just 2.5 % in 2010. Non-resident hunters remained fairly consistent over last decade at about 5000 individuals per year, but fell 20 % during the recent economic crisis. Between 1998 and 2012, the number of residents hunting black bears in the GBF study area declined from 198 to 65, while the number of resident grizzly bear hunters fluctuated between a high of 60 and low of 20, with 47 in 2012. Over the same period, the number of guide outfitters has been small, fluctuating between four and seven companies, with four companies operating in 2012. |

| 6. The relatively low economic contribution of bear hunting and the declining hunter numbers in the Province as a whole come at a time when bear hunting is losing popular support as well, both in Canada and abroad. In September 2013, a poll by McAllister Opinion Research poll found that 87 % of British Columbians support a ban on trophy hunting for bears in the Great Bear Rainforest, up from 73 % in a similar survey in 2008. Further, the survey found that 91 % of BC hunters agree that hunters should respect First Nations’ laws and customs within First Nations’ territory. In addition, the European Union’s ban, beginning in 2001, on importation of grizzly bear trophies from BC has effectively stopped European hunters from coming to the province to hunt grizzlies although a small percentage still come to hunt black bears. In addition, since late 2005, bear-viewing proponents have bought the exclusive territories from three hunting guide outfitters, thereby successfully halting non-resident hunting of grizzlies in these areas which include a large swath of the central coast. |

| |

|

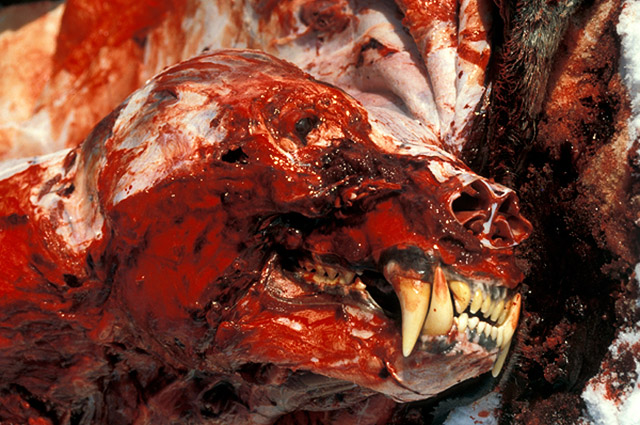

| Grizzlybär im Great Bear Rainforest |

© Klaus Pommerenke |

|

| |

| 7. The 2013 MFLNRO-commissioned [Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations] study conducted by Responsive Management, Expenditure of British Columbia Resident Hunters, suggests resident hunter expenditures reached $230 million in 2012. However, its findings raise questions and its estimates appear inflated in a number of areas. A study by BC STATS for the year 2003 estimated resident hunter expenditures at $70 million, and since then the number of resident hunter licenses declined from 160,000 to just under 80,000 in 2012, according to MFLNRO statistics. A threefold increase in expenditures since 2003 contrasts strongly with a 50 % decline in people hunting and it suggests that there may be some errors in the results. In addition, the 2013 study may have overinflated the number of hunter days and spending per day, and since these feed directly into the calculation of total expenditures, one must question the validity of the total expenditure estimate of $230 million. These apparent errors may be due to the fact that the study accepted the telephone responses as stated and did not benchmark to any known data. For example, total licenses and tags (specie licenses) for the province are estimated at just over $9 million in the study, whereas according to MFLNRO, the actual value of licenses and tags collected was only approximately $6.0 million for 2012, a value roughly 65 % of the study’s estimated value. Given these uncertainties, it is not really possible to say how accurate the 2013 study is. |

| 8. Whatever the actual amount generated by resident hunting in BC and the GBF (an amount this report questions as inflated), this spending represents a circulation of already existing money rather than new money entering the province. Resident dollars spent on hunting are dollars not available to be spent on other goods and services and therefore, as most economists would advise, resident hunting should be viewed as providing no substantive economic impact to the BC economy. |

| 9. Even assuming that resident hunting actually contributes to the economy, it is also true that non-resident grizzly hunting has a higher economic contribution rate than does resident grizzly hunting ($244,600 in non-resident grizzly GDP for four kills or $61,000 per kill compared to $60,000 for resident grizzly GDP for six kills or $10,000 per kill). |

| 10. The BC government’s administrative apparatus overseeing bear hunting is complex, cumbersome, and costly. The MFLNRO technical team that provided data for this study said they had no information on the cost of managing bear hunting, but several officials indicated that the government is spending more on bear hunting management than it is receiving from bear hunting. The current system includes a mixture of different categories designated for hunting – Limited Entry Hunting (LEH) areas, guide areas, guide territories, Wildlife Management Units (MUs), Grizzly Bear Population Units. etc. – that frequently overlap and make it difficult to determine where bear kills actually occur. In addition, because the BC government does not recognize the GBF as a legal geographic entity, it does not collect any bear-hunting data specific to this region. The data and maps provided by MFLNRO’s technical team were based on Management Units and LEH areas, some of which extended beyond the GBF borders. Further, the government compiles only estimates (often with wide variances in percentages of accuracy) on the number and location of black bears killed by hunters. Only grizzly bear kills are officially tracked via a compulsory reporting system, and even here data in the government’s own spreadsheets were, on occasion, inconsistent. The government’s management and monitoring systems therefore proved unable to answer the basic question: How many bears are hunted and killed each year within the Great Bear Rainforest?“ |

Die komplette 129-seitige Studie finden Sie unter: www.responsibletravel.org/projects/documents/

Economic_Impact_of_Bear_Viewing_and_Bear_Hunting_in_GBR_of_BC.pdf |

| |

| Im September 2012 hatten die Coastal First Nations in BC bereits einseitig die Trophäenjagd auf Bären in ihren angestammten Territorien verboten (vgl. Meldung vom 07.10.2012 auf dieser Website), doch die Provinzregierung sprach ihnen das Recht hierzu ab und ignoriert dieses Verbot bis heute, indem es Trophäenjägern ausdrücklich erlaubt, auch in diesen Gebieten Bären zu töten. Doug Neasloss, Ratsmitglied der Kitasoo/Xai’xais First Nation von Klemtu, sagte zur neuen CREST-Studie: „This study reinforces what First Nations in the area have been saying for years. Bears are worth more alive than they are dead. That goes for our communities, the ecosystems on the coast, and now we find out it’s true for the B.C. government, too.“ „I’ve worked as a bear viewing guide for the past three seasons“, sagte Jason Moody von der Nuxalk First Nation. „Those numbers reflect what we’re seeing, for sure. There’s so much potential for tourism and hospitality, but trophy hunting is holding things back and that makes it harder for First Nations to create jobs for our people that are in line with our laws and our traditions.“ |

| Eine Meinungsumfrage vom September 2013 (McAllister Opinion Research – die Namensgleichheit mit Ian McAllister von Pacific Wild ist zufällig, beide Institutionen haben nichts miteinander zu tun) ergab, dass 87 % der Einwohner von BC es unterstützen, dass die Trophäenjagd auf Bären im Great Bear Rainforest beendet wird. Eine nachfolgende Meinungsumfrage eines anderen Instituts (Insides West) fand, dass 88 % der Einwohner von BC die Trophäenjagd ablehnen. 95 % der Jäger in der McAllister-Umfrage stimmten der Aussage „You should not be hunting if you’re not prepared to eat what you kill“ zu. Jessie Hausty vom Stammesrat der Heiltsuk First Nation meinte zur aktuellen Studie: „This latest study raises an important question for B.C.’s minister responsible for hunting, Steve Thomson. Last fall, we learned the science used to justify the bear hunt is deeply flawed. Now we see the economics are completely backward. So will Thomson do the right thing and bring B.C. government policy in the line with First Nations law? Or will he let trophy hunters take more money out of taxpayers’ pockets?“ Erst im November 2013 zeigte eine Studie, dass im Zeitraum zwischen 2001 und 2011 regelmäßig mehr Grizzlybären getötet wurden, als es im offiziellen Grizzly Bear Management Plan des Ministeriums vorgesehen war. Diese „overkill“-Studie bewies, wie verfehlt die angeblich wissenschaftliche Datenbasis ist, auf welche sich das Ministerium bei der Berechnung der jährlichen „Tötungsquote“ von Grizzlybären beruft (vgl. Meldungen vom 10. + 11. November 2013 auf dieser Website). |

| |

|

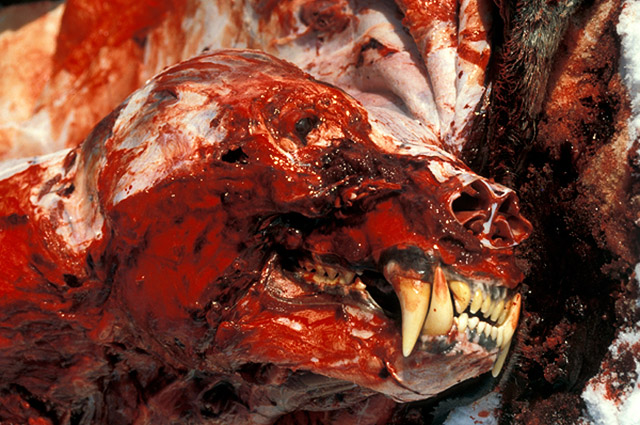

| Trophäenjäger haben einen getöteten Bären gehäutet – das blutige Geschäft der Trophäenjagd |

© Klaus Pommerenke |

|

| |

| Steve Thomson sieht in der Jagd (einschließlich der Trophäenjagd) und der Fallenstellerei eine „amazing opportunity to appreciate our province’s wild spaces, and the creatures that dwell in them“ (Minister’s Message, Hunting and Trapping Synopsis 2012-2014, S. 2). Das Genießen von Wildnis und das Beobachten von Wildtieren reduziert er bewusst auf Jagderlebnisse. Das Beobachten von Wildtieren ohne gleich einem niederen Tötungsimpuls wie bei der Trophäenjagd zu verfallen, scheint für ihn offensichtlich unvorstellbar. Ein Wertschätzen unberührter Landschaften und der darin lebenden Tierwelt ohne Jagd ist für ihn nicht denkbar, das eine geht für ihn ohne das andere nicht. „Hunting not only provides recreational opportunities for residents of the province who appreciate nature and enjoy the experience of being in the outdoors, it also augments British Columbia’s tourism industry, further spreading the word around the globe of our exceptional wilderness.“ Im Lichte der neuen CREST-Studie werden seine Worte als falsch, ja als bewusst irreführend entlarvt. Auch seine Aussage „hunting and trapping support the economy“ in seiner Minister’s Message ist weit von der Realität entfernt. Das Gegenteil ist der Fall, der Bärbeobachtungstourismus bringt der Provinz weit mehr ein als die rückläufige und ethisch längst von einer überwältigenden Bevölkerungsmehrheit geächtete Trophäenjagd. Steve Thomson, Cheflobbyist der finanzstarken Jagdindustrie, stellt sich in seinem Ministerium ganz in deren Dienste. Seine Ziele: „Encouraging more people to take up hunting“, „Developing a new expanded Youth Hunting Licence and creating an Initiation Hunting Licence“ (Minister’s Message, Seite 2). Die Rekrutierung neuer Jäger soll schon bei 10 bis 13-jährigen Kindern ansetzen. Bereits sie sollen eine Einführungs-Jagdlizenz erhalten und in einer Art „Initiationsritus“ für die Jagd begeistert werden. Jeder mag sich selbst ein Bild von der Persönlichkeit eines Ministers mit derartigen Rekrutierungsplänen machen. Man soll Kinder frühzeitig in ihren Talenten fördern und sie auch zu sportlichen Aktivitäten animieren, aber das ministeriale Fördern einer als Sport missverstandenen Jagdleidenschaft einschließlich einer Leidenschaft für das Lusttöten bei der Trophäenjagd kann auch ein Hinweis auf das Vorhandensein einer gewissen Psychopathologie sein. Es wäre an der Zeit, dass Premierministerin Christy Clark die Abberufung des Ministers Steve Thomson erwägt. |

| |

zurück zurück |

|

|